Progress on New Federal Electronic Instructional Materials Accessibility Legislation

Published by: WCET | 9/21/2015

Tags: Accessibility, Digital Learning, Disabilities, Distance Education

Published by: WCET | 9/21/2015

Tags: Accessibility, Digital Learning, Disabilities, Distance Education

In today’s blog post, we have a conversation with Jarret Cummings, EDUCAUSE’s Director of Policy and External Relations. Jarret has helped lead negotiations on new federal legislation that would facilitate the development of voluntary accessibility guidelines for electronic instructional materials and related technologies in higher education. We thank Jarret for this update as part of a series of webcasts and blogs during WCET’s accessibility month.

Russ Poulin: Jarret, you’ve been part of the ongoing discussions regarding the accessibility of educational technologies in higher education. EDUCAUSE, your organization, the American Council on Education, and other higher education associations have been working with the National Federation of the Blind (NFB) and the Association of American Publishers (AAP) on new legislation. The discussions seek to find a compromise position among organizations with diverse constituencies on the development of voluntary accessibility guidelines for postsecondary electronic instructional materials and related technologies. What started this process and how has it unfolded?

Jarret Cummings: Thank you for inviting me to discuss this, Russ. I really appreciate it. In terms of the genesis of the process, NFB and AAP began collaborating in 2012 on a bill that they named the Technology, Equality, and Accessibility in College and Higher Education—or TEACH Act. It was an outcome of the Postsecondary Accessible Instructional Materials Commission that Congress chartered under the last reauthorization of the Higher Education Act. That Commission looked at instructional considerations related to higher education and developed some recommendations.

One of the Commission’s recommendations was that the federal government foster the development of voluntary accessibility guidelines for instructional materials in the postsecondary space. Following the release of the Commission’s report, NFB and AAP started working on a bill to implement that recommendation. They were able to have the bill introduced into the U.S. House of Representatives in late 2013 and subsequently in the U.S. Senate early last year. EDUCAUSE, along with a number of other higher education associations, took a look at the proposal and felt that it actually would not lead to the voluntary guidelines it was intended to produce. We chartered an expert analysis to determine if those concerns were valid, and it confirmed the problems we thought we saw in the bill.

One of the Commission’s recommendations was that the federal government foster the development of voluntary accessibility guidelines for instructional materials in the postsecondary space. Following the release of the Commission’s report, NFB and AAP started working on a bill to implement that recommendation. They were able to have the bill introduced into the U.S. House of Representatives in late 2013 and subsequently in the U.S. Senate early last year. EDUCAUSE, along with a number of other higher education associations, took a look at the proposal and felt that it actually would not lead to the voluntary guidelines it was intended to produce. We chartered an expert analysis to determine if those concerns were valid, and it confirmed the problems we thought we saw in the bill.

When we started sharing the results of our analysis with the broader higher education community and others, we unfortunately ran into some miscommunication with NFB and AAP about the nature of our concerns. We were trying to get across that we shared the goals of the original legislation, but didn’t think the bill, as then constructed, would lead to workable, voluntary guidelines. Once we got past that initial miscommunication, we were able to sit down with NFB and AAP and agree to work together on a joint bill that would establish a process for developing the guidelines that all three communities could support.

On behalf of a number of other higher education associations, a small team from ACE and EDUCAUSE has been working with NFB and AAP representatives since late last year to develop a joint legislative proposal. We started by developing a shared concept outline for the bill, which we finished earlier this summer, shared with a range of stakeholder groups, and then revised based on their feedback. Since late July we’ve been working on translating that concept outline into an actual bill. The process is well underway; we’re actively working on edits as we speak. Hopefully, we will be able to release a public draft of the bill later this fall.

Russ: I’m taken by the term “voluntary” guidelines. Why have those negotiating the bill focused on “voluntary” guidelines and how do those organizations see those guidelines coming together?

Jarret: I think AAP and NFB focused their initial legislative proposal on voluntary guidelines because they recognized how fluid and complicated a space this is. As you know, the range of disciplines and pedagogical considerations that electronic instructional materials and related technologies must address in higher education is extremely broad as well as extremely deep. A rigid regulatory approach to try to advance accessibility in that context would likely generate significant unintended consequences that could limit the availability and effectiveness of teaching and learning with technology for all students, including students with disabilities.

So, on the higher education side, we thought the original idea that NFB and AAP had about addressing these issues through voluntary guidelines was a good one. In our view, voluntary guidelines would raise awareness and inform decision-making while also preserving institutional flexibility to meet students’ unique needs.

Taking that as our starting point, AAP and NFB joined us in agreeing that the process needed to be more clearly stakeholder-led and stakeholder-driven. One reason this matters from a higher education perspective is that any discussion of instructional materials and technologies necessarily involves pedagogy. The higher education community wanted to make sure that the process for producing effective voluntary guidelines wouldn’t negatively impact institutional oversight of the teaching and learning mission, which the federal government has long agreed should remain higher education’s responsibility. A stakeholder-led process with equal representation from higher education leadership ensures that the guidelines will develop in a balanced, well-informed context, which will also ensure that institutions genuinely have the flexibility they need to meet student needs to the extent they reasonably can.

Russ: Given that negotiations are still ongoing, what else can you say about what we’re likely to see in the bill that will be submitted to Congress?

Jarret: I think the most important point about the bill is that it isn’t intended to set the voluntary guidelines itself. Rather, it’s designed to create a process for developing voluntary guidelines for postsecondary instructional materials and related technologies that the major stakeholder groups involved can all agree will successfully do that. As envisioned, it asks Congress to charter an independent commission with equal representation from the disability advocacy community, publishers and technology producers, and the higher education community. The resulting commission will have about 18 months to two years to produce guidelines with the support of a technical expert panel, which itself will also have equal representation from each community.

Another important aspect of the process is that the guidelines will not recreate the wheel when it comes to IT accessibility standards. There are already well-established national and international standards, such as for web accessibility. We don’t need to develop general IT accessibility standards specific to higher education. If anything, that would probably severely complicate the ability of higher education to produce accessible environments because the marketplace for digital content and technologies is quite large. In some sense, when you think about the overall market for publishing and technology, higher education is not that big a piece of the pie. Separating higher education off into its own sphere, specifically for technology accessibility, would probably be fairly detrimental to us all, because it would limit the applicability of materials, technologies, and innovations in the broader market to higher education, and vice versa. All of the groups realize that there are aspects of pedagogy that might lead to considerations about accessibility that fall between the gaps of these general standards. The idea is that the commission will look at these general IT accessibility standards in relation to pedagogical needs and concerns and develop voluntary guidelines to help institutions, publishers, and technology producers bridge those gaps.

I think another benefit of the process is that the bill will call for the commission to leverage its review of those general standards to also produce a reference list of general IT accessibility standards. Included will be notes for institutions on how those standards might apply to specific needs in the higher education context.

Russ: These efforts all arose out of a concerns regarding how well colleges serve students with disabilities. In focusing on those students, how will these guidelines benefit them and the institutions that serve them?

Jarret: I think the guidelines will give institutions, as well as publishers and technology providers, more information with which to address accessibility needs in relation to teaching and learning in higher education. Current law recognizes that not all disability needs can be addressed in a general manner, given the unique requirements that an individual disability may pose in a given context. This is especially true in relation to a particular discipline, how that discipline is taught, and what materials and technologies are used to support that teaching and learning process.

So, in short, the guidelines will help institutions make decisions about adopting materials and technologies that take accessibility into account to the extent possible, which in turn will better enable institutions to help students with disabilities achieve their academic goals.

Russ: Great! Do you have any recommendations about what colleges should be doing now or how they can keep updated on the progress of your joint proposal?

Jarret: First, I would encourage everyone to participate in the EDUCAUSE Live! webinar that I’m conducting on September 22nd with my colleague Jon Fansmith from ACE. We’re going to discuss the current state of the process in greater detail and what we think the likely outcomes are.

I also provide updates via the Policy Spotlight blog on the EDUCAUSE Review website. Those updates cover major developments in the process and, as I mentioned earlier, we’re hopeful that later this fall we’ll actually have a public draft of the bill to share. Once we do, the Policy Spotlight blog is probably one of the first places that information will become available.

In terms of what institutions should be doing now, I think it’s important for institutions to assess the accessibility of their technology environment generally and on a regular basis to make sure that they’re in compliance with current law and regulation. Institutional personnel may want to look at some of the consent agreements that other colleges have entered into with the U.S. Departments of Education and Justice and groups like NFB to help inform their thinking. The background slides for a panel on “accessibility in the cloud” that I moderated at the 2015 Internet2 Global Summit highlight a few examples. I would also encourage anyone with questions about how to assess their institution’s approach to IT accessibility to get in touch with the EDUCAUSE IT Accessibility Constituent Group. Group members are IT accessibility professionals representing a wide range of colleges and universities, and they’re always happy to help colleagues at other institutions.

Russ: WCET can also help with that as we’re set to host a webcast on September 29 about “turning a negative into a positive.” Accessibility leaders who helped Penn State University (although he’s now at Rutgers) and the University of Montana in creating new strategies to serve disabled students will give their advice on what colleges should be doing.

Jarret: That’s great – Penn State and Montana have been very proactive since they came to fully understand the issues that led to their consent agreements. I think they’ve really embodied the spirit that higher education generally is striving to achieve in this area. By and large, institutions involved in consent agreements just didn’t have a complete awareness of the nature of their accessibility problems and what those problems meant for their students. Once they did, they’ve generally taken the responsibility to address those problems very seriously, and others can learn a great deal from their example.

Russ: Agreed. Jarret, on behalf of our members, thank you for your work in negotiating the new bill. And thank you for updating us on its current progress. We look forward to hearing more in the future.

Director, Policy and External Relations

EDUCAUSE

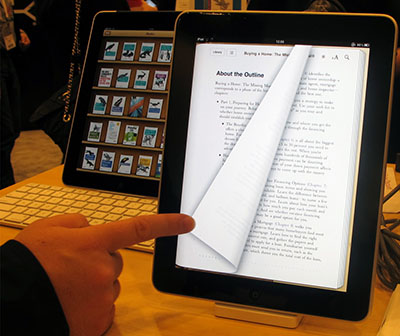

Photo Credit: Anita Hart